- About Us

- Policy Center

- Learn

- Press Room

- Blog

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Donate to J Street Online

- Make a Gift in Someone’s Honor or Memory

- Make a Monthly Gift

- Tax-Deductible Donations

- Giving by mail

J Street’s blog aims to reflect a range of voices. The opinions expressed in blog posts do not necessarily reflect the policies or view of J Street.

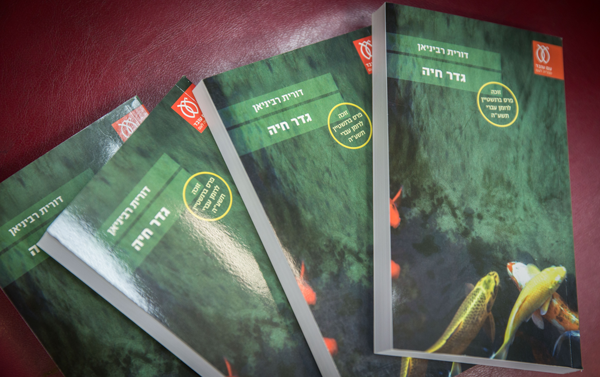

On December 30th, the Israeli Ministry of Education, headed by Minister Naftali Bennet from the Jewish Home party, banned the book Borderlife by Dorit Rabinian from being taught in high schools around the country. The book depicts an affair between an Israeli Jewish woman and a Palestinian Muslim man.

According to the Ministry, the book was inappropriate for high schoolers because Israel needs to protect “the identity and cultural legacy of the students from all parts of society,” because “intimate relations between Jews and non-Jews allegedly threaten the various individual identities” and because “teenagers lack the broad vision and consideration necessary to maintain their cultural identity and to understand the meaning of cultural assimilation.”

The head of literature studies in the Ministry of Education, a ministry committee on literature and a panel of veteran teachers had all recommended that the book be taught to advanced literature students prior to Bennet’s ban.

I was skeptical of the ministry’s decision even before I read the book. After finishing, I confess that I am even more baffled.

I think that the Ministry’s concerns about the book encouraging relationships between Jews and non-Jews are problematic in themselves. But even if, for the sake of the argument, I thought their objections were valid, they would be wrong to ban this book.

Rabinian shows us — relentlessly throughout the book — how hard it is for an Israeli-Palestinian couple to have a normal relationship, even when both parties are sympathetic to each other’s narratives. In fact, I would argue that after reading the book, one might think that it is impossible to manage a “long distance relationship” between Tel-Aviv and Ramallah – two cities that are 30 miles and a separation barrier apart.

After drawing this conclusion — and I find it difficult to draw any other — one must ask themselves what it is in the book that caused the Ministry of Education to ban it – a rare step in Israel. The only answer I can come up with is that they were concerned about the book’s humanizing personification of Palestinians. If students realize that Palestinians are actually similar to them — that they have the same feelings, fears and ambitions — then they might actually start thinking of them as human-beings and not as menial workers at best, or terrorists at worst.

That sort of humanistic thinking is concerning to right-wing elements in within a government that thrive on fear of the “Other” — a fear that is rooted in a lack of knowledge and understanding between Israelis and Palestinians.

Without fear of the “Other,” Israeli youth might just understand the “meaning of cultural assimilation,” and grasp the importance of coexistence — which may be exactly what the ministry is afraid of.

Summary of the Book

Liat, an Israeli woman in her late 20’s, is a translator living temporarily in New York city. She came to NY for a period of six months and plans to return to Israel.

Hilmi, a Palestinian man born in Hebron whose family currently lives in Ramallah, is a painter living in the US under an artistic visa.

Liat and Hilmi (or Hilmic — as Liat calls him in a Hebrew-like nickname) meet via a mutual friend and stay together until Liat returns to Israel.

The author goes to great lengths to show how difficult it is for Liat to acknowledge the fact that she’s involved with Hilmi. At the beginning Liat tells herself that she’s going to end the relationship but finds it impossible. When they discuss the political issues, it turns into a brutal fight. Even though Liat testifies that she had always considered herself a leftist, she couldn’t accept Hilmi’s positions that the land should be shared by the two peoples and that the two-state solution is a fantasy. They ultimately decide not to discuss politics.

The fact the the love story occurs in New York is very important – it enables the Liat to build their relationship without taking the complexities of the conflict into consideration. In New York, they can avoid discussing politics and Liat can opt not to tell her family and friends about Hilmi. In contrast, Hilmi sees the relationship as a long term one – they are madly in love, her friends in the US love him, he loves them and his family is supportive.

Liat and Hilmi are both complicated characters; neither is defined defined by their love story. Their relationship seems incredibly strong when it stands alone, but Liat is certain that it can’t continue in the “real world.” She says: “It’s strange, because of the time difference, it’s like everyone back home in constantly asleep… whenever I wonder what my parents are doing now I imagine them sleeping… It’s like my life is happening while everyone is sleeping.”

In fact, one could say that the couple lived inside a bubble made possible by their physical distance from the region. It’s not that the conflict doesn’t exist inside that bubble, it does — but being so far away lets them “manage the conflict” and not allow it affect their relationship.

They confront an interesting reality check when Hilmi’s brother comes to visit and engages Liat in a fierce political argument. Every Israeli knows the feeling of being the only Israeli at the table and feeling like you have to be the ambassador for your country. The debate ends up driving Hilmi and her apart. It’s a fascinating glimpse into the destructive power that the political reality holds over their relationship, and how easily the bubble that they’ve created can burst.