- About Us

- Policy Center

- Learn

- Press Room

- Blog

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Donate to J Street Online

- Make a Gift in Someone’s Honor or Memory

- Make a Monthly Gift

- Tax-Deductible Donations

- Giving by mail

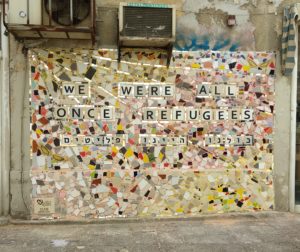

J Street’s “Our Israel” project spotlights the amazing Israeli groups who share our progressive vision for Israel, and who are helping build a society underpinned by the founding values of democracy, self-determination and equality which are enshrined in Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

In 1998, journalist Einat Fishbain was working on a story about new migrant workers in Israel. The article, titled The New TelAvivians, described these communities’ daily lives and struggles.

The piece was published, but she knew she wasn’t done with the story. It turned into a regular column, and she created a phone number for migrants to call and leave a message about their personal experiences.

Calls started flooding in, yet there was an issue. Many of the migrants – most of whom were calling from detention centers – spoke various languages other than Hebrew.

Three women across Israel followed the columns and reached out to Fishbain to ask how they could help. Fishbain connected the three women. The women then recruited a network of volunteers who could speak different languages, and in turn provide aid to migrants. That’s how the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants was born.

“In the first decade or so, the hotline focused primarily on migrant workers in detention and completely transformed the way migration detention is handled. Back then, it was a no man’s land – people were held in detention for months and months without seeing a judge,” Executive Director of the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants Dr. Ayelet Oz explains. Oz, who has been with the Hotline since 2019, notes the ways in which the organization had an impact in those early days.

Before 2001, The Entry to Israel Law allowed for indefinite detention of noncitizens coming into the country. The Hotline women saw the conditions these migrants were facing – unable to ask for help after being detained, struggling to understand their legal status and the resources available to them, and ineligible for legal representation or assistance from the State.

Thanks in large part to the work of the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants and other NGOs, the Detention Review Tribunal was established in 2001. The government created the Tribunal to allow migrants to make their case within fourteen days of being arrested, and stipulated that the State could only issue a detention order after they had the chance to do so.

The creation of the Tribunal was the first of many successes for the organization. Yet as they visited more and more migrants in detention centers, they began to confront an issue that was not getting enough attention.

Trafficking in Israel

As volunteers continued speaking to those in detention centers, they met many women who told them stories different from the narratives they had heard about foreign workers. “The women said: we did not say we come there to work. We were kidnapped. We were taken to brothels and held against our will,” Oz says. “They became the first people to document trafficking for the sex industry in Israel.”

The volunteers collected over 400 affidavits from women, and started pushing the government to take action. Throughout the 2000s, they managed to transform trafficking law in Israel completely. In 2006 Israel passed its Anti-Trafficking Law – the first of its kind in the country.

While tremendous progress has been made, trafficking in Israel remains a problem.

“At that time, we were talking mostly about trafficking for the sex industry from Eastern Europe. Since the mid-2000s, that problem has drastically declined,” Oz explains. “It’s not like it was back then when you could picture what a trafficked woman looked like. Today, it’s much more diverse and much harder to see. So we actually spend a lot of our time identifying and coming to terms with new modes of trafficking.”

One form of trafficking that the Hotline focuses on is helping foreign women who have been forced into marriages with Israeli spouses. It becomes nearly impossible for them to get divorced, as they risk losing their visas and deportation. In these situations – which Oz refers to as trafficking by marriage – there is often severe domestic violence at play.

According to Israeli workers rights organization Kav LaOved, despite increasing reliance on migrant labor in Israel, the State has failed to establish acceptable anti-trafficking prosecution, protection and prevention measures.

Recently, the Israeli government approved a new plan to combat human trafficking. The decision came on the heels of an annual US State Department report, which concluded that Israel is not doing enough to prevent human trafficking and does not fully meet the minimum standards for eliminating trafficking.

A Harsh Reality for Asylum-Seekers

As the nature of human trafficking in Israel began to shift at the end of the first decade of the Hotline’s work, a new phenomenon in the country emerged. “Around 2009-2012, African refugees started entering Israel from the southern border,” Oz notes. As a result, the Hotline, which had previously been called “The Hotline for Migrant Workers,” changed its name to encompass the influx of refugees.

“There was mass detention of asylum seekers in Israel. As the only NGO who had access to those migration detention facilities, we represented thousands and thousands of people in detention,” Oz tells J Street.

The process for seeking asylum is painstakingly slow. Since signing the Refugee Convention almost 60 years ago, Israel has recognized less than 1% of asylum claims – compared to 10-50% in other developed countries. There was a time when Israel’s refugee recognition was the lowest percentage in the Western world. While laws have been passed on paper to mitigate these problems, there has been very little progress in reality.

“What happens is that most of the community lives in this never-ending limbo because they are not deported, but they’re not acknowledged as refugees. So they just stay in this underclass for 10 or 15 years,” Oz explains. “This is the core of the problem of where we are today – and we are fighting as hard as we can to change it.”

One reason for Israel’s harsh refugee policies? “A lot of people are motivated by the fear of Israel losing its Jewish identity,” Oz reflects.

Polling backs this up. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and an influx of Ukrainian refugees to Israel, the Israel Democracy Institute found the issue of non-Jewish refugees to be controversial and polarizing. Conservative respondents, who make up the majority of the Israeli public, were largely unlikely to support the unlimited entrance of non-Jewish refugees into the country.

Right-wing lawmakers such as Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked, who has primarily shaped the country’s refugee policy in recent years, warned that an influx of non-Jewish refugees could challenge Israel’s status as a Jewish-majority country.

“This fear isn’t backed up by facts,” Oz notes. “We’re talking about fewer than 30,000 refugees, which is in no way a demographic risk. I know many fear that if we’re welcoming, many more will come. I do not think that this threat is founded. On the other hand, welcoming refugees – as we once were – upholds central values of what being a Jewish country means to me.”

Working for Change

What started as a Hotline has evolved into much more. The Crisis Intervention Center is what Oz calls the “descendant” of the original work of its founders. It’s the part of their work where they have the most direct contact with the community.

This aspect of their work has also evolved past just a place to call, as they host weekly meetings for asylum seekers where they provide free counseling, host trips for those who can’t reach their office in Tel Aviv and hold women-only reception hours.Over the years more than 750 volunteers have been involved in this work and thousands of migrants have been released from detention as a result.

The volunteers work in tandem with the legal staff. Hotline lawyers represent individual clients, and work on cases aimed at setting or changing precedents within the Detention Tribunal and all the way up to the Supreme Court. Their successes have led to a whole host of changes: from legislative reforms, to the establishment of state funded legal aid, to housing and medical care for trafficking victims.

They use their work within these communities to reform immigration policy. “We see our connection with the community as what gives us both legitimacy and urgency to change policy, because we see all those affected by it,” Oz explains.

Through research and policy papers, media activism, public events, and meetings with stakeholders and decision makers, they educate and inform the public about immigration policy and its implication – establishing them as a prominent public advocacy organization.

“We believe in changing reality not only through decision-makers but by harnessing the power of the public. It’s a difficult fight, but it’s an important one that we believe in.”

To learn more about the Hotline for Refugees and Migrants visit their website.