- About Us

- Policy Center

- Learn

- Press Room

- Blog

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Donate to J Street Online

- Make a Gift in Someone’s Honor or Memory

- Make a Monthly Gift

- Tax-Deductible Donations

- Giving by mail

J Street is proud to stand with pro-peace Israeli organizations who do amazing work to create a better future for Jewish Israelis, Arab Israelis and Palestinians. As part of a series of profiles focused on our progressive partners, we sat down with co-founder of Hand in Hand Lee Gordon, who helped create Israel’s largest integrated school network.

It was November 1995, and Lee Gordon’s son was perched on his shoulders as Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin spoke at a historic peace rally. “I wish to thank each and every one of you who have come here today to take a stand against violence, and to stand for peace,” Rabin told the crowd.

Rabin spoke of the legacy he hoped to leave his children and grandchildren, insisting that he had found a partner for peace in the Palestinians and that the time for courageous action was now. It was the last speech the Prime Minister ever made. “He finished and we turned to leave,” Gordon says, “he was shot walking down the stairs.”

Rabin’s assassination by a far-right fanatic marked the beginning of the end for Israel’s once-powerful peace movement and the unraveling of the Oslo peace process. But for Lee Gordon, it redoubled his commitment.

Two years after the assassination, Gordon had joined with Arab-Israeli educator Amin Khalaf to work on an ambitious new co-existence project — they would found and operate an integrated, Arab-Jewish school. Each class would have teachers from each background, lessons would be conducted in both Hebrew and Arabic and parents would be encouraged to become part of a broader, integrated school community. One of their early supporters was J Street President Jeremy Ben-Ami, who assisted with strategy and communications planning.

“It didn’t really exist at the time,” Gordon says. “There were regions where Jews and Arabs were living right across the street from each other — literally next door — but there were no integrated schools.”

But what began with just 55 students has now grown to the largest integrated school network in the country, with roughly 2,000 students across six schools. From struggling to attract students when they started out, Hand in Hand now has a waitlist of over 1,000 children. Two Arab members of the Knesset send their kids to the schools and the organization has attracted high-profile supporters internationally, including the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Although Hand in Hand has gone from strength to strength, integrated schools remain somewhat of a novelty in Israel. “Right now, every school is like a little startup,” Gordon says. “We’re still a bit of a well-kept secret, even though we don’t want to be.”

When they started out, Gordon and Khalaf knew one of the main challenges would be attracting an equal number of both Jewish and Arab students. In a Hebrew-speaking, majority Jewish society, the pair knew that Arab parents would be eager to give their kids a ticket into mainstream society and the upward mobility that it would bring. The incentive for Jewish parents was less clear.

Initially, Jewish parents were driven by values and ideology, with many of them having been active in the peace movement. Today, however, there’s much broader appeal — the schools have a strong track record of academic merit and a low teacher/student ratio, a result of each class having both an Arab and Jewish teacher.

In early grades, Hand in Hand gives students set seating plans, alternating between Jewish and Arab children. In later years, that’s no longer necessary. National or religious holidays are optional, and each is treated as an opportunity for dialogue. Role-playing exercises encourage participants to argue from the other’s perspective. “At our schools, students don’t lose their identity,” Gordon says. “In many ways, it strengthens their identity.”

Integration doesn’t stop at the school gate either — each school makes a concerted effort to build wider communities that involve parents as well. Dialogue sessions encourage parents to tell their family’s stories, often the first time they have done so to a mixed audience. It can be an empowering, moving experience.

“All of a sudden, people are listening,” says Nadia, an Arab Israeli mother of two students featured in a Hand in Hand case study. “People are connecting over pain, over sadness. It doesn’t matter who, it doesn’t matter on what side. All of a sudden, we’re together.”

When the Israeli-Palestinian conflict flares up, joint discussion sessions are held not only for students but parents too. “Everybody speaks and everybody listens, nothing is taboo,” Gordon says. The goal isn’t to debate or to win, but to listen with respect.

“One of the advantages of us discussing these things in the school is that everyone already has these strong bonds,” Gordon says, “they have this common denominator, their kids go to school together.”

For Arab students attending Hand in Hand schools, the integrated environment is somewhat of an oasis from a more tense and divided society. “What I hear, especially from students, is that this is a place where they feel safe,” Gordon says.

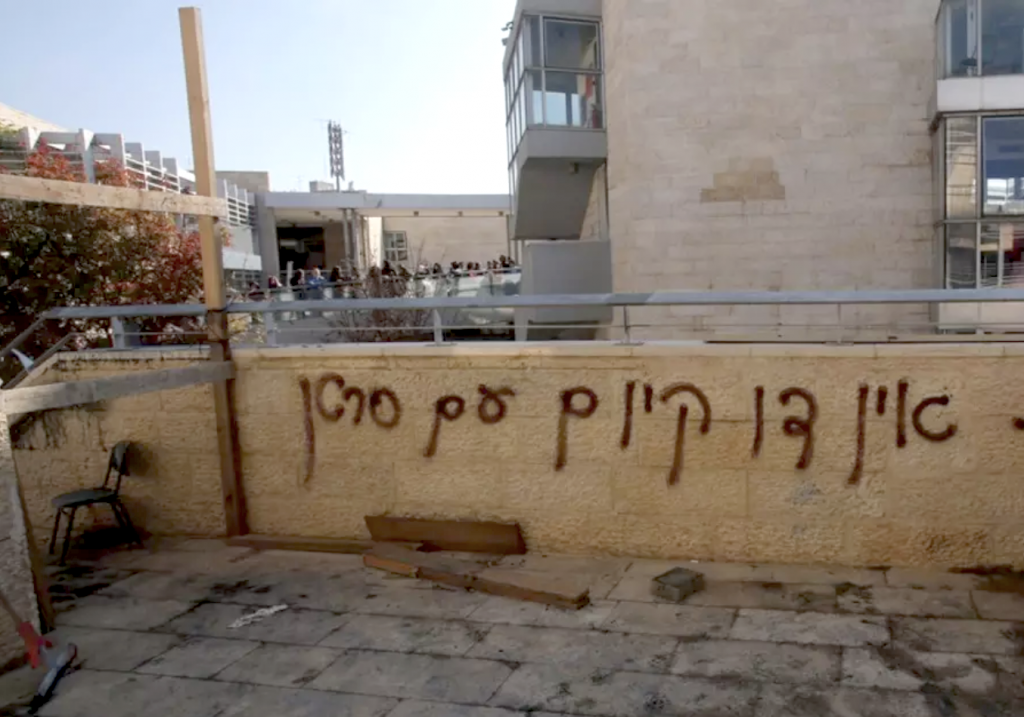

But that doesn’t mean the outside world doesn’t sometimes intrude on the school community. Arab students have faced suspicion within their own communities for attending an integrated school. An Arab-speaking student on a bus was once slapped by a woman who demanded they speak Hebrew. In 2014, “Death to Arabs” was spray-painted repeatedly on school facilities. The community responded by hanging a banner saying: “There is cooperation, love and friendship here between Arabs and Jews.” Three weeks later, arsonists burnt down a classroom and scrawled “there is no coexistence with cancer” on the walls.

But with support from the school, and from their integrated friendship networks, Gordon says Hand in Hand students have proven resilient and united in the face of such attacks.

The idea of integrated schooling inherently makes a lot of sense to people, Gordon says, even to the point of crossing fraught political divides. “I talk to people who are not J Street supporters, who go to AIPAC conferences, and they say this makes sense to them, that of course Jews and Arabs should go to school together,” Gordon says. “They may not know much about the situation but this makes sense to them, and I love that.”

“We are the pioneers of a different reality, a better one,” says Tamar Borman, a Jerusalem Hand in Hand graduate featured on the group’s website. “When they say peace can’t work, I tell them it’s been working for more than a decade.”

“I think a lot of people see our schools as a sign of hope,” Gordon says, “I like to think that Hand in Hand is a little model of what Israel could look like.”

J Street is at the forefront of a political movement to push back against the Trump-Netanyahu agenda and lay the groundwork for a new era of progressive, values-driven diplomacy-first American leadership.