- About Us

- Policy Center

- Learn

- Press Room

- Blog

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Donate to J Street Online

- Make a Gift in Someone’s Honor or Memory

- Make a Monthly Gift

- Tax-Deductible Donations

- Giving by mail

J Street roots our work in a commitment to and support for the people and the state of Israel. Our mission highlights our desire for Israel to be a secure, democratic national home of the Jewish people, which guarantees equality for all citizens.

“Our Israel” is a J Street initiative which spotlights amazing Israeli organizations and individuals who share our values and who struggle, as we do in America, to build and preserve a liberal, democratic society underpinned by the principles of equality, freedom, justice and peace. These leaders, advocates and organizations work tirelessly to build a better future for all of Israelis and for their Palestinian neighbors. They are on the front lines of the struggle to build a society that lives up to the founding values and ideals enshrined in Israel’s Declaration of Independence.

![Palestinian women protest against home demolitions in the 'unrecognised villages' of Israel's Negev region [Reuters]](https://jstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Screen-Shot-2020-10-09-at-3.53.32-PM-1024x680.png)

Women protest against home demolitions in the ‘unrecognized villages’ of Israel’s Negev region.

When I ask Dr. Yeela Raanan what it’s like to watch a family’s home be demolished, the normally unflappable Bedouin rights campaigner has to pause for a moment to gather herself. “Oh god,” she says, voice catching in her throat. “They’re very, very violent. You can’t demolish a house in a non-violent way.”

In her work with the Regional Council for the Unrecognized Villages in the Negev, Dr. Raanan has been to too many demolitions. “There is just a huge amount of police, they have hundreds of police in full riot gear. There are babies crying and mothers crying. Everybody stands and looks at it as the bulldozer starts demolishing their home,” she tells J Street. “You just watch it happen, there’s nothing you can do.”

“When you destroy someone’s home you destroy their world, their future, their hope,” says Attia Alasam, the democratically elected chair of the regional council. “It produces hatred and alienation from state institutions, and from the government that destroyed their house.”

Of Israel’s 200,000 Bedouin citizens, roughly half live in the country’s south in 35 villages which remain officially unrecognized by the Israeli government. Despite living in nomadic communities on the land for thousands of years, the villages’ unrecognized status places homes and infrastructure under constant threat of demolition, with the government generally denying access to the most basic utility connections and social services.

For Bedouin Israelis who live in recognized townships, socio-economic indicators are not much better. Successive governments have pursued policies to push the nomadic tribes into contained urban townships. The result has been high levels of unemployment, stunted economic development and a loss of cultural heritage. “We find many parallels in our struggle and other indigenous peoples’ struggles,” Alasam tells J Street.

“It’s a culture created from the time of Abraham to adapt to huge, vast spaces, and they want to cram them into these towns,” Dr. Raanan says.

“Ultimately, our goal is for the state to treat us as equal citizens and treat us equally in the allocation of resources, and in fundamental rights,” Alasam says. “I want the state to allow us to preserve our traditional way of life and our traditional customs, and to preserve our Bedouin heritage.”

It’s a straightforward vision, but it remains at odds with Israeli government policies which continue in attempts to transfer Bedouin communities off their traditional land to make way for Jewish settlements. In 1963, military leader and Minister of Agriculture Moshe Dayan summed up the government’s approach nakedly, telling Israeli newspaper Haaretz of the plan to “transform” the Bedouin people from nomadic tribes into urbanized workers.

“This will be a radical move which means that the Bedouin would not live on his land with his herds,” Dayan told the newspaper. “It may be fixed within two generations. Without coercion but with government direction, this phenomenon of the Bedouins will disappear.” Subsequent governments have sought to more honestly grapple with the challenge of providing services, dignity and justice to Bedouin communities, but progress remains limited.

Homes and infrastructure in unrecognized Bedouin villages continue to be destroyed by government authorities, which refuse to provide basic services for tens of thousands of Bedouin citizens.

The regional council, which operates as a democratic body modeled after Israel’s formal regional council system, has advocated for Bedouin rights and recognition since 1997. In that time, the group has won a series of bureaucratic and legal battles to connect several villages with health, education and infrastructure services. In 2003, after intense, ongoing advocacy, the Israeli government formally recognized eight additional villages.

Dr. Raanan says progress has been uneven and slow. Under the Netanyahu government, she worries that progress stalled altogether. As a Jewish Israeli herself, she says it’s striking for Israel, of all nations, to show such indifference to cultural erasure. “Whether it’s Australia or the United States or anywhere else, governments, in general, don’t like nomadic or semi-nomadic people, and certainly don’t do well with indigenous people,” she says.

Despite the frequent demolitions, Dr. Raanan has never grown numb to emotional impact. The most traumatic demolition she attended left two men dead and ignited a national scandal.

“It was dark, we couldn’t see, we could only hear it happen,” Dr. Raanan says, describing the night in January 2017. Dr. Raanan remembers standing alongside prominent Arab-Israeli parliamentarian Ayman Odeh when they heard shouting, screams that people had been injured.

In harrowing aerial footage which has since been made public, Israeli police are seen to open fire on a 47-year-old man, Yaqoub Abu al-Qia’an, as he drives back to his house to collect his belongings before the demolition. A bullet shatters the man’s knee, causing his leg to spasm and sending his car accelerating wildly into a crowd of officers who scramble and scatter. The incident left the school teacher dead, along with 34-year-old police officer Erez Levi.

A police officer opens fire on a Bedouin school teacher returning to collect items from his home before it is demolished.

Dr. Raanan, who knew al-Qia’an personally, was devastated by the killing and appalled by the authorities’ response. As her group ran to the scene to assist, they were forced back by officers who shot at them with sponge-tipped bullets. “They pepper-sprayed straight to the face, including Ayman,” she says. “They just let Yaqoub bleed out.”

Within hours, a police spokesman and Benjamin Netanyahu, Prime Minister at the time, had made official statements branding the school-teacher a terrorist who needed to be neutralized. Three years later, Prime Minister Netanyahu would apologize for the mistake.

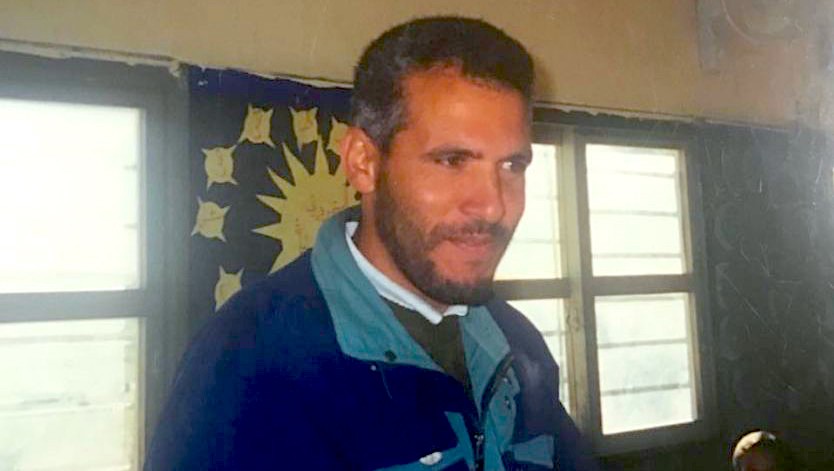

47-year-old school teacher Yaqoub Abu al-Qia’an.

“Not only did you demolish his house, not only did you kill him and rob his children of a father and make his wife a widow, but you made him a terrorist as well,” Dr. Raanan says in despair.

While welcoming the apology, Alasam says it was too little, too late. “A state commission of inquiry should be set up to investigate the affair, to bring it to an end and to prevent such incidents from happening in the future,” he says, urging accountability at every level, from the police officers on the ground to the minister in charge. “Only then will the apology have weight and meaning.”

While the government justifies demolitions with reference to planning policy, Dr. Raanan says it’s just cover for an intentional policy of displacement. “Planning policy is used quite cynically to say that you’re not registered, so you don’t have any rights to the land,” she says.

It’s a strikingly similar battle to the one playing out just a few miles to the north between Palestinians and Israelis in the occupied West Bank.

“When the Israeli authorities demolish, or force people to demolish, homes and sources of livelihood, they typically cite a lack of Israeli-issued building permits,” UN Humanitarian Coordinator Jamie McGodrick said in a recent statement. Such permits, however, are “almost impossible” for Palestinians to obtain due to the Israeli government’s “restrictive and discriminatory planning regime,” McGodrick said.

Demolitions on the West Bank are also justified by a planning permit regime, which operates to deny Palestinians access to their land.

In both cases, the Israeli government pushes individuals to ‘self-demolish’ with threats to charge families with the cost of government demolitions. In both cases, demolitions have paved the way for Jewish settlements. “The main difference is that the Bedouin are citizens of Israel,” Dr. Raanan says, “so they’re using democratic means to fight for recognition. In the West Bank, it’s a nationalistic fight.”

Chairman Alasam agrees, noting that it hasn’t stopped the government from portraying the Bedouin people as outsiders. “The government portrays us as fighting a national struggle against the state, with the aim of depriving us of the legitimate civil rights as equal citizens,” he says. “I’m happy we have so many Jewish partners that understand that our equal rights are everyone’s equal rights.”

For Alasam, this message of inclusion, equality and unity is fundamental to the struggle. “We want to be an integral part of the State of Israel while maintaining our special character and heritage as Bedouin,” he says. “It is important to me that the Israeli public does not see us as enemies.”

It’s a vision for Israel he hopes can unite Bedouin Israelis, Jewish Israelis and diaspora Jews around the world. “We share the vision of a successful and prosperous Israel, an Israel that welcomes the wide diversity of all citizens in the country and allows them equal rights,” he says. “We share a desire to see Israel as a model state of acceptance of the other, of multiculturalism and a thriving democracy — We want to be equal citizens in our own country.”