- About Us

- Policy Center

- Learn

- Press Room

- Blog

- Get Involved

- Donate

- Donate to J Street Online

- Make a Gift in Someone’s Honor or Memory

- Make a Monthly Gift

- Tax-Deductible Donations

- Giving by mail

During my trip to Israel last month, I visited the Palestinian village of Susya. I wanted to meet the villagers and see it with my own eyes. Even though I grew up only 30 minutes away, I had never been to or met anyone from Susya.

© Gili Getz, 2016

It was around the time that B’Tselem head, Hagai Elad, stirred up Israeli politics when he testified before the UN security council. In his testimony, he argued that the 50 year old occupation is not exclusively an internal Israeli matter and called for international pressure to help end it.

In doing so, he touched on a blind spot in Jewish Israeli society. A blind spot that for too many Israelis makes Palestinian suffering invisible and prevents them from seeing the occupation. A blind spot that prevents them from seeing Susya.

© Gili Getz, 2016

The villagers of Susya, located in Area C — which includes 60 percent of the West Bank and is under full Israeli military and civilian control — are among the poorest people in the West Bank. In 1986 they were forced out of their homes, where they had lived for generations, to make way for an Israeli archaeological dig. Left homeless, they moved a few hundred meters away onto the farmland that they own. In 2001 the village was once again demolished. The entire village continues to live under the threat of demolition.

© Gili Getz, 2016

Our community took number of effective steps. J Street mobilized thousands to call on the State Department to condemn the demolition. Rabbi Rick Jacobs, The President of URJ, issued a courageous call to prime minister Netanyahu to “protect the village of Susya from destruction.”

© Gili Getz, 2016

I arrived in Susya with the amazing activists from the The Center for Jewish Nonviolence. Their action this summer on behalf of diaspora Jews “Occupation is not our Judaism,” during which we celebrated g Sabbath in Susya was deeply inspiring.

As we approached the village I noticed The entire drama was unfolding in front of my eyes. On the one side of the Palestinian village was a thriving, beautiful Jewish settlement also called Susya, founded in 1983. On the other side of the village is the site where the Palestinians used to live, but were evicted to make room for an arecholeological dig.

© Gili Getz, 2016

It was harvest time and the villagers and some French volunteers were busy picking and sorting olives.

We had a conversation with Nasser Nawaja, protected by the olive trees from the sun, about the bureaucratic nightmare the Civil Administration subjects them to. When your entire life can be demolished at any moment, and not for the first time, it’s a difficult struggle.

© Gili Getz, 2016

The Israeli High Court at one point ordered a stay on the demolitions and allowed the residents to remain on the site. However, the court did not mandate that the Civil Administration issue construction permits or recognize any planning rights.

© Gili Getz, 2016

After discussing the unimaginable life of a community that was destroyed again and again, we found ourselves talking about Jewish American politics, how it’s changing and all the work being done by Jewish American youth to fight the occupation.

© Gili Getz, 2016

After more conversation with residents of the village and the volunteers from France, I asked Mohamed, a young kid, to show me around the village. He introduced me to his dog and his friend and was very excited to show me the chicken coop (also under demolition order).

© Gili Getz, 2016

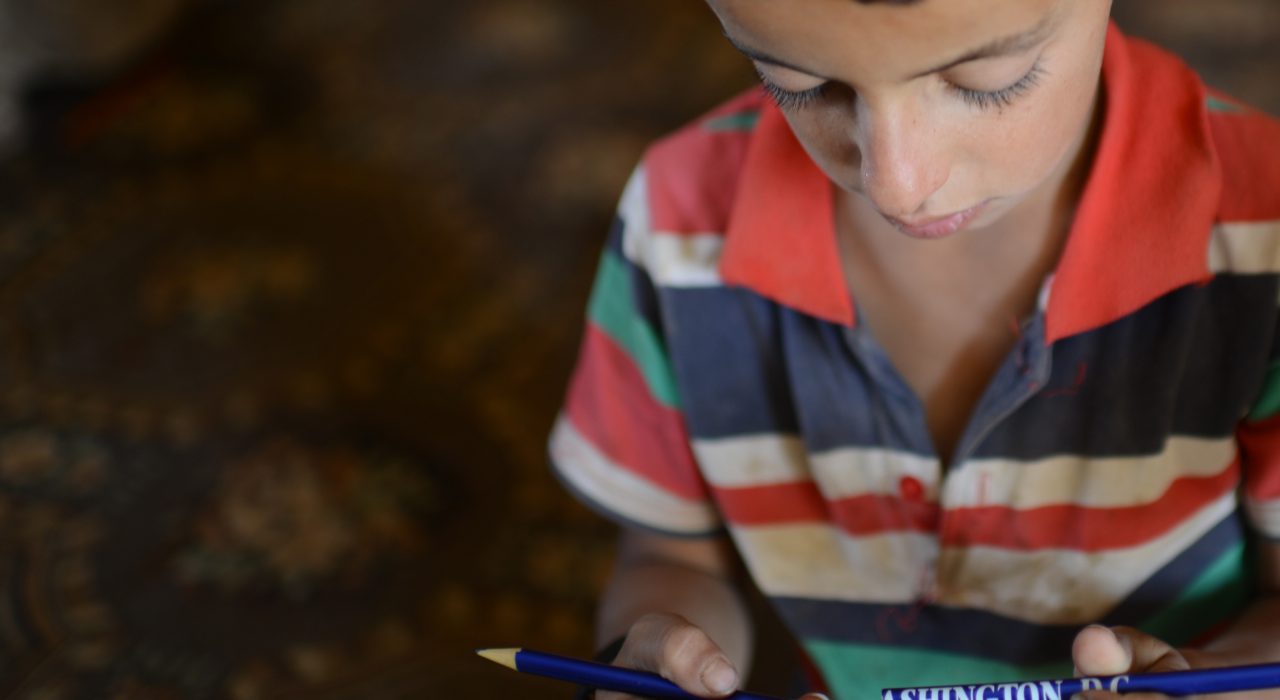

When we walked to his tent we met another kid. This one was more suspicious of me, telling me to leave and not hurt his family. After what he had been subjected to I couldn’t blame him. After a few minutes of conversation, we convinced him that I was okay. Ahmad wanted to show me his toys and was super excited that I knew who Dora the Explorer was. The other kid showed us his pencil with “Washington DC” written on it. Probably given him by one of the international delegations that stops there to “see Susya for themselves.” It was broken. Washington is broken. Very appropriate.

© Gili Getz, 2016

After tea I was invited to talk to Fatma Nawaja. Fatma founded the Rural Women Association, a non-profit organization founded to raise women’s voices in marginalized and remote areas of Palestine.

Fatma told me about her daily life with no running water, school project to raise money and organizing women to support each other. This was definitely the highlight of my visit. The grace, toughness, resilience and incredible spirit Fatma embodies when speaking of a life under a constant threat of demolition made a deep impact on me.

© Gili Getz, 2016

Our next stop was the village of Umm al-Kheir. Umm al-Kheir is another Palestinian village in the South Hebron Hills just eight kilometers north of Susya. We visited with the villagers and talked to Eid Suleman over tea. Umm al-Kheir didn’t get the international attention Susya received and once again faces a new round of demolitions. Their homes and EU-funded community center were reduced to rubble. The village is located just a few feet away from the Jewish settlement Carmel that is constantly expanding.

© Gili Getz, 2016

As Israel receives funding and diplomatic protection from the international community to help the state with its security needs and regional threats, so too should it accept outside input and help to protect its democratic character and the prospect of a two-state solution to the conflict.

I vowed to come back in May 2017, and participate in The Center for Jewish Nonviolence action in Susya that will include Jewish activists from around the world, as part of the 9 days of solidarity work with Palestinians who are being evicted from their homes. Join me.